Commercial motor vehicle (CMV) operators can have a dramatic impact on vehicle efficiency and overall fuel consumption. The skill with which a driver controls a vehicle, the frequency of idling and average vehicle speed all play a role in how efficiently a vehicle is operated. An ATRI study found “eco-driving” training or coaching for drivers was used by more than half of the fleets that participated in the study and was the second most mentioned fuel-saving strategy being considered for deployment in the following year.[1]

Driving Practices

Research has shown that carriers can improve fleet fuel economy by training drivers to operate vehicles more efficiently. Drivers play a key role in obtaining the best possible fuel economy from their trucks since they control factors such as idle time, brake use, vehicle speed, and route selection. For example, a report completed by the American Trucking Associations’ (ATA) Technology and Maintenance Council found a 35 percent difference between the most and least efficient drivers.[2] According to this report, the most fuel efficient drivers were consistently found to:

- Maintain a high, but not maximum, average speed;

- Operate a high percent of the trip distance in top gear;

- Utilize cruise control when possible;

- Minimize the amount of time spent idling; and

- Minimize the number of sudden decelerations (hard braking) and accelerations.

A recent update of the Technology and Maintenance Council’s Best Practices report includes additional measures such as:

- Maintaining proper tire inflation pressure;

- Using progressive shifting;

- Limiting the use of vehicle accessories; and

- Ensuring even load distribution between drive and trailer tires.[3]

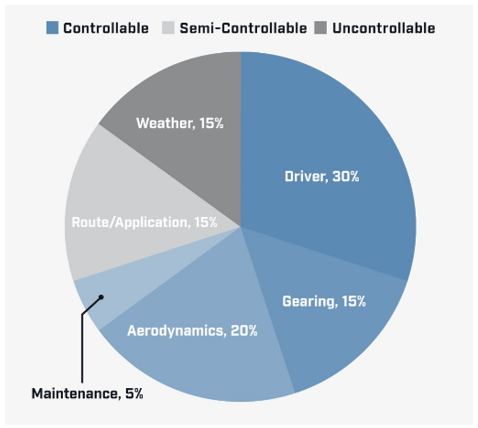

Drivers can also influence fuel consumption through appropriate route selection. Drivers and/or dispatchers should take geography, weather and regional considerations into account when determining a route or setting a schedule. As shown in Figure 1.1, weather and routing account for nearly one-third of the factors affecting fuel economy while the driver and vehicle account for the other two-thirds.[4] Drivers who make strategic decisions concerning vehicle maintenance, operational decisions concerning engine idling and break use, and tactical decisions concerning route selection and vehicle load have accounted for up to 20% of fuel consumption reductions.[5]

Figure 1.1. Factors Affecting Fuel Economy

Driving Training and Incentives

Studies from other countries have demonstrated that driver training can benefit carriers by increasing fuel efficiency and reducing costs. For example, a study conducted by the European Commission found that a one-day driver training course could result in a fuel efficiency increase of five percent.[6] In addition, Canadian researchers found that for combination truck drivers, training and driver monitoring could result in a 10 percent fuel efficiency increase.[7]

To develop the skills necessary for improving vehicle fuel efficiency, fleets may opt to use a variety of training techniques including classroom, online, in-cab and/or driving simulator-based programs. Further carriers indicate that training is not a “one-size-fits-all” solution therefore they offer a variety of training options to their drivers such as online and in-cab training, driver management systems, driver monitoring and in-person coaching.

Strayer and Drews studied the fuel efficiency of drivers before and after simulator training that focused on optimizing shifting practices and techniques.[8] The researchers found that after a two-hour training course, study participants were able to increase fuel economy by an average of 2.8 percent. Using this average, if a vehicle consumes $50,000 of diesel annually under normal operating conditions at a diesel average price of $3.06, this two-hour training course could result in a $1,400 savings per year per driver.

Research sponsored by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) reported that driving simulators typically cost $125,000 to $290,000, depending on the model and vehicle configuration used.[9] Based on this initial equipment price and factoring in a service life of 15 years and typical maintenance, the price of simulator training can therefore range between $3.37 and $5.07 per student per hour.[10] It should be noted however, that there are industry vendors that offer mobile simulator classrooms that can reduce simulator training costs.

In another study, Symmons and Rose examined the influence of classroom training on truck driver behaviors related to fuel consumption in Australia.[11] Participants in this study drove a cement truck on an on-road test track (approximately 30 kilometers or 19 miles) in which their fuel consumption, completion duration, gear changes and brake applications were measured. Twelve participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions:

- Control: Did not receive any pre-training or classroom instruction.

- Classroom-only: Participants completed a one-hour classroom course on progressive braking, progressive gear shifting, scanning the road, torque and power curves.

- Fully trained: Participants completed the same one-hour classroom course as the classroom-only participants, but also completed a pre-drive of the on-road test track prior to the classroom instruction.

Prior to the classroom course, fully trained participants consumed an average of 26.4 liters (7 gallons) of fuel while completing the test track. Post-classroom instruction, fully trained participants consumed an average of 19.2 liters (5.1 gallons) of fuel, a 27 percent decrease. Other results from the study indicated that six weeks after training, participants in the fully trained condition consumed less fuel (statistically significant) than drivers in the classroom-only and control conditions. On average, fully trained participants consumed 20.1 liters (5.3 gallons) of fuel, classroom-only participants consumed 26.8 liters (7.1 gallons) of fuel and control participants consumed 27.5 liters (7.3 gallons) of fuel while completing the test track. The findings from this study suggest that there was indeed a transfer of training for classroom instruction with potential positive benefits experienced through increased fuel efficiency.

In another example, the Upstate Niagara Cooperative deployed a hybrid training program which consisted of in-cab coaching (via telematics), classroom instruction and targeted training of poor performers to overcome the issue of fuel inefficiencies.[12] The in-cab telematics provided both the driver and their supervisor with information on the driver’s driving habits such as fuel efficiency or shifting patterns; in addition the system would alert the driver when they engaged in inefficient driving behaviors. In the first three months after deploying the in-cab coaching, seven out of ten trucks demonstrated marked improvement. Prior to the coaching, the average fuel economy was 5.81 miles-per-gallon (mpg), post-coaching the average fuel economy increased to 6.10 mpg.[13]

Boodlal and Chiang conducted a study evaluating the influence of coaching and telematics systems on safety and fuel efficiency behaviors among 46 drivers who drove Class 8 day and sleeper cabs.[14] The research included four conditions: a control day cab group; a control sleeper cab group; a pilot day cab group; and a pilot sleeper cab group. Interventions were introduced to drivers in the pilot day and pilot sleeper cab groups between November 2010 and October 2011. The interventions were carried out via five stages:

- Baseline data measurements were collected.

- Drivers in both pilot groups were informed that researchers were collecting truck performance data to measure safety and fuel economy.

- Drivers in both pilot groups were provided with weekly vehicle information such as revolutions per minute, speed and fuel consumption. This same information was also provided to fleet managers.

- Drivers in both pilot groups were informed that their driving behavior was monitored via telematics and if drivers engaged in unsafe driving behaviors they were alerted via in-cab telematics.

- Drivers in both pilot groups were rated on safety measures, but not on fuel economy measures. Drivers with poor safety scores received coaching from their fleet managers on problem areas (e.g., excessive hard braking or speeding).

- Drivers in both pilot groups continued to receive feedback from fleet managers; however, the researchers introduced monetary incentives to drivers with the best safety improvement and fuel economy improvement.

- At the conclusion of Stage 5 the researchers continued to collect driver safety and fuel economy measures but ceased all interventions to determine if performance gains could be sustained over time.

While the fleet managers did not specifically address fuel economy during the driver coaching sessions in Stage 4 or 5, the researchers indicated that fuel economy could be increased via the safety coaching and alerts the drivers received because behaviors such as excessive speeding or harsh accelerations can reduce fuel efficiency. Therefore, the researchers hypothesized that driver monitoring and coaching would help to improve fuel economy. Results from the analyses indicated that drivers in the pilot day cab group had an average baseline fuel economy of 7.07 mpg while at Stage 5 (monetary incentives) these drivers had an average fuel economy of 7.77 mpg.

Likewise, drivers in the pilot sleeper cab group had an average baseline fuel economy of 7.04 mpg while at Stage 5 these drivers had an average fuel economy of 7.42 mpg. The researchers concluded that for the duration of the study the coaching, in-cab alerts and incentives were effective in increasing fuel economy across both the pilot day and sleeper cab groups however additional research should be completed to determine the lasting effects of these interventions to a period of 30 to 60 months post-intervention.[15]

Trucking companies may also offer fuel bonus programs to drivers that incentivize fuel conservation. Such programs typically pay drivers on a per mile basis if a certain fuel economy is reached over the course of a month. For example, Nussbaum Transportation deployed technology to measure and collect driver data metrics related to fuel efficiency that are then used to calculate a driver fuel scorecard.[16] The driver fuel scorecard is used to determine if a driver has exceeded the fleet’s mpg goal which then assigns a driver one point for every 0.01 mpg exceeded. Drivers are presented with monetary awards based on the number of points they accumulate and according to a predefined three-tier bonus system:

- Bronze: Drivers in this tier receive $0.50 for every point earned.

- Silver: Drivers in this tier receive $5.00 for every point earned.

- Gold: Drivers in this tier receive $8.00 for every point earned.

As an alternative to the three-tier system, Nussbaum Transportation awards drivers up to $0.05 per mile for every point earned.[17]

The aforementioned research findings and carrier practices demonstrate that increases in fuel efficiency can be achieved through a variety of training methods, driver monitoring and use of incentives. In addition to increased fuel efficiency, each of these training methods may also increase driver safety behaviors that further contribute to trucking industry sustainability.

[Back to top]

Another way that drivers can improve fuel efficiency is by limiting idling time. Drivers idle their truck engines for a variety of reasons including to power in-cab accessories, provide heating or air conditioning, and to ensure that the engine fuel and oil remain warm in cold weather conditions. Past research has estimated that an idling truck consumes approximately 1 gallon of fuel per hour and increases both air and noise pollution.[18] It has been estimated that more than 6 billion gallons of gasoline and diesel are cumulatively lost to idling every year.[19]

An idling reduction technology has three general characteristics: 1) is installed on a vehicle or at a location; 2) reduces main engine idling; and 3) provides services to the vehicle or equipment that would otherwise require the operation of the main engine while the vehicle is stationary or parked.[20] There are a number of idle reduction devices on the market including:

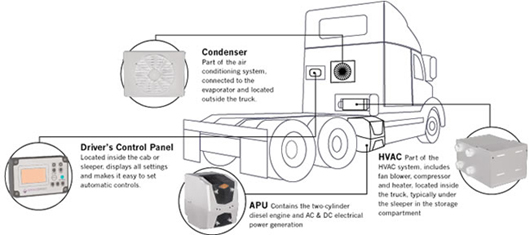

Auxiliary power units – APUs are used for heating, air conditioning and/or electrical power to the truck cab. There are two main types of APUs available: diesel-powered and battery-electric. A diesel-powered APU consists of a small internal combustion engine equipped with a generator and alternator and provides electricity to power a heater, air conditioner and/or in-cab accessories. Due its smaller engine, a diesel-powered APU uses a fraction of the fuel when compared to idling a truck’s main engine. Battery-electric APUs are designed so that the main engine charges the batteries during normal driving operations and then provides when the engine is turned off. This technology eliminates fuel consumption during idling but operational time is limited by battery energy storage capabilities. Diesel-powered and battery-electric APUs can save 80 percent or more of the fuel consumed during idling but have a relatively high upfront cost of $7,000 to $12,000 per unit.[21]

- Fuel-operated or direct-fired heaters– Fuel-operated or direct-fired heaters can be used to heat the interior of the cab, the engine or both and range in cost from $900 to $1,500.[22] These heaters generally burn less than 0.1 gallons of fuel per hour while an idling diesel engine will consume between 0.6 to 1 gallon of fuel per hour.[23] On average a fuel-operated air heater will use approximately a gallon of fuel during a 24-hour period. Air conditioning is not provided by these devices.

- Truckstop electrification– TSE provides trucks with power through two mechanisms: on-board or off-board electricity. In the on-board application, trucks are equipped with an embedded electrical hardware system and can be “plugged in” to an external power source to provide heating and cooling and to power in-cab accessories. Off-board systems provide heating and cooling infrastructure as well as electrical plug-ins at the truck stop or rest area, typically through an overhead hose connection which is inserted in the side window. While these services are generally provided for an hourly fee (commonly $1-3 per hour), off-board systems do not require the purchase or installation of any additional electrical or climate control equipment.[24]

In addition to these idle-reduction technologies, educating drivers about the impacts and adverse effects of long-duration idling can help reduce idling time as can offering financial incentives. Some state, city and local governments are also attempting to minimize environmental impacts by offering incentive funding to help offset the cost of purchasing vehicles which incorporate alternative technologies such as idle reduction.[25] A number of jurisdictions have also promulgated laws that limit the length of time an engine can idle. As these regulations vary widely, a compendium of idling regulations has been compiled by the American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI).[26]

[Back to top]

The travel rate at which drivers operate their vehicles is another key factor in improving fuel efficiency. While every vehicle reaches its optimal fuel economy at a different speed, fuel economy typically decreases rapidly at speeds above 50 to 55 miles per hour (mph). For example, when compared to 75 mph, traveling at 55 mph saved 28 percent more fuel while driving at 65 mph saved 15 percent more fuel. And while lower speeds do increase travel times, maintaining a 65 mph speed increases travel times just 15.5 percent.[27]

Individual carriers can lower the maximum speeds of their entire fleet through the use of speed limiters (also known as speed governors) which are devices that interact with the engine to prevent the truck from exceeding a pre-defined speed. Since speed governors are installed on all large truck engines manufactured after 1992, carriers simply have to activate the devices and incur no additional cost. An ATRI study found speed limiters to be one of the top fuel-saving technologies currently being employed by fleets.[28]

An assessment performed by Transport Canada found that a national speed limiter mandate of 105 kilometers per hour (65 mph) could save Canadian carriers up to C$200 million ($184 million U.S.) annually through reduced fuel consumption.[29] Since the assessment, two Canadian provinces: Ontario and Quebec have passed speed limiter legislation.[30] As noted, limiting fleet speed can be a low or no-cost fuel-saving strategy for carriers since the majority of large truck engines have these devices pre-installed and simply need to be activated.

Operating vehicles at consistent speeds also improves fuel efficiency. An analysis performed by ATRI evaluated the potential fuel consumption and emissions impacts of operating a vehicle on two roughly parallel routes of approximately 70 miles in Maine.[31] One route was a state highway that had several signalized intersections. The second route was an interstate highway that had no stoplights but was approximately five miles longer. Despite the longer travel distance of the second route, total fuel consumption was an average of 1 to 2 gallons less compared to the state highway route. While this particular study modeled a higher productivity vehicle (at a gross vehicle weight of 100,000 pounds), these findings support the importance of maintaining a consistent speed in order to improve fuel efficiency.

[Back to top]

[1] Schoettle, Brandon, Sivak, M., and Tunnell, M. (October 2016). “A Survey of Fuel Economy and Fuel Usage by Heavy-Duty Fleets” Available online: https://truckingresearch.org/2016/10/17/a-survey-of-fuel-economy-and-fuel-usage-by-heavy-duty-truck-fleets/

[2] Technology and Maintenance Council. (2008). “A Guide to Improving Commercial Fleet Fuel Efficiency.” American Trucking Associations, Arlington, VA.

[3] Technology and Maintenance Council. (2021). “Recommended Best Practices Manual 2020 – 2021.” American Trucking Associations, Arlington, VA.

[4] Detroit Diesel. “Demand Great Fuel Economy.” Available online: https://demanddetroit.com/why-detroit/fuel-economy/

[5] Huertas, J. I., et al. (2018). “Eco-driving by replicating best driving practices.” International Journal of Sustainable Transportation 12.2: 107-116.

[6] Whistler, D. (2011). “Fuel Economy 101.” FleetOwner Magazine. Available online: http://fleetowner.com/fuel_economy/fuel-economy-0701

[7] Ibid.

[8] Strayer, D.L. and F.A. Drews. (2003). “Simulator Training Improves Driver Efficiency: Transfer from the Simulator to the Real World,” Proceedings of the Second International Driving Symposium on Human Factors in Driver Assessment, Training, and Vehicle Design, Park City, Utah, pp. 190-193.

[9] Virginia Tech Transportation Institute. (2010). “Commercial Motor Vehicle Driving Simulator Validation Study: Phase II.” Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, Washington, D.C.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Symmons, M.A., & Rose, G. (2009). “Ecodrive Training Delivers Substantial Fuel Savings for Heavy Vehicle Drivers,” Proceedings of the Fifth International Driving Symposium on Human Factors in Driver Assessment, Training and Vehicle Design, pp. 46-53.

[12] Lockridge, D. (2011). “Private Fleets Find Fuel Savings in Changing Driver Behavior,” TruckingInfo. Available online: http://www.truckinginfo.com/channel/fuel-smarts/article/story/2011/10/private-fleets-find-fuel-savings-in-changing-driver-behavior.aspx

[13] Ibid.

[14] Boodlal, L., & Chiang, K., H. (2014). “Study of the Impact of a Telematics System on Safe and Fuel-Efficient Driving in Trucks.” Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, FMCSA-13-020.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Huff, A. (2014). “Performance-Based Pay, Part 1: The Science of Scoring Drivers,” Commercial Carrier Journal. Available online: http://www.ccjdigital.com/performance-based-pay-part-1-the-science-of-scoring-drivers/

[17] Ibid.

[18] Stodolsky, F., et al., (2000). “Analysis of Technology Options to Reduce the Fuel Consumption of Idling Truck.” Argonne National Laboratory.

[19] Argonne National Laboratory. “Idle Reduction Benefits and Considerations.” Available online: http://www.afdc.energy.gov/conserve/idle_reduction_benefits.html

[20] United States Environmental Protection Agency. “Learn About Idling Reduction Technologies (IRTs) for Trucks and School Buses.” Available online: https://www.epa.gov/verified-diesel-tech/learn-about-idling-reduction-technologies-irts-trucks-and-school-buses

[21] Penske Truck Leasing, Cut Costs. (June 2018). “Increase Driver Satisfaction with Auxiliary Power Units” Available online: https://www.pensketruckleasing.com/resources/industry-resources/auxiliary-power-unit/

[22] North American Council for Freight Efficiency. (2014). “Confidence Report on Idle-Reduction Technologies.”

[23] North American Council for Freight Efficiency. (2019). ”Confidence Report on Idle-Reduction Solutions.”

[24] Millard-Ball, A. (2009). “Truck Stop Electrification and Carbon Offsets.” Climate Action Reserve.

[25] United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2021). “National DERA Awarded Grants.” DERA. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/dera/national-dera-awarded-grants

[26] American Transportation Research Institute. Compendium of Idling Regulations. Available online: https://truckingresearch.org/2020/03/16/idling-regulations-compendium/

[27] Bridgestone Americas Tire Operations, LLC. (2009). “Does Speed Kill?” Real Answers. Volume 13, Issue 3.

[28] Schoettle, Brandon, Sivak, M., and Tunnell, M. (October 2016). “A Survey of Fuel Economy and Fuel Usage by Heavy-Duty Fleets.” Available online: https://truckingresearch.org/2016/10/17/a-survey-of-fuel-economy-and-fuel-usage-by-heavy-duty-truck-fleets/

[29] Transport Canada. (July 2008). “Summary Report – Assessment of a Heavy Truck Speed Limiter Requirement in Canada.”

[30] Government of Canada. “Summary Report – Assessment of a Heavy Truck Speed Limiter Requirement in Canada.” Transport Canada. Available online: https://tc.canada.ca/en/summary-report-assessment-heavy-truck-speed-limiter-requirement-canada

[31] American Transportation Research Institute. (2009). “Estimating Truck-Related Fuel Consumption and Emissions in Maine: A Comparative Analysis for a 6-axle, 100,000 Pound Vehicle Configuration.” Maine Department of Transportation. Available online: https://truckingresearch.org/2009/09/17/estimating-truck-related-fuel-consumption-and-emissions-in-maine-a-comparative-analysis-for-a-6-axle-100000-pound-vehicle-configuration/